Invasive Aquatic Plant Survey 2015

by Cheryl Savery

On July 7th 2015, Terry Demers and I conducted a survey of the North Branch of Buck Lake looking for invasive aquatic plants. We were specifically looking for any of 8 aquatic plants that have been found in or near other Ontario lakes. (More details about these plants can be found in the May 2015 newsletter.) Whenever we saw anything that we thought might be an invasive plant, we took pictures and noted the GPS coordinates. All the data was then submitted into EDDMapS (Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System). We found several plants that looked to us like it might possibly be water hyacinth. Before any information was stored in the system, experts reviewed the images to verify that we had made a correct assessment. As it turns out, the plants were all pickerel weed. This was very good news, as it is growing in many locations on both branches.

|

|

|

In August, Martha Scheinman and I repeated the process for the South Branch. We noted some of the areas where Eurasian water-milfoil was growing, but that was the only invasive aquatic plant we found. There were some plants that we thought could have been yellow iris, but there were no flowers so we could not tell what the plants were.

We are fortunate that Buck Lake is relatively free of invasive plants, however it will take constant vigilance by all users of the lake to keep it that way. Remember, if you move your boat between lakes, simple steps like pumping out the bilge water and drying and inspecting your boat before putting it back in the water can help keep invasive plants from entering the lake.

Although a survey like this was good for getting an initial picture of the state of the entire lake, it is much more effective if everyone is keeping an eye on their little corner of the lake. If you notice any unfamiliar plants anywhere on the lake, please contact BuckLakeAssoc@nullgmail.com and we will happily investigate it further. If invasive species are detected early, there are resources available in the province that can assist in removing the plants, before they take over the lake.

Wild Parsnips

Many of our residents, and visitors to the Buck Lake area, are aware of Wild Parsnip, but for those who need some information on this invasive and dangerous plant, the following is provided.

Wild Parsnip, or Poison Parsnip, is quickly moving into our region and is now endemic to many areas around Ottawa, Leeds-Grenville, Kingston and westward to Napanee. Very large patches are now clearly visible along the 401 roadsides, especially now in July that the plant is over a meter tall and in its soft yellow bloom.

What follows is a distillation of information on this invasive and toxic plant, and there are many informative web sites on the topic, some of which I have listed below.

Wild Parsnip can be found spreading into open areas. What looks like a colourful wildflower is actually a toxic plant that could burn your skin and hurt your eyes. It grows into large patches along roadsides, abandoned fields, rail tracks and trails, and around sports fields, pastures and fence rows.

The weed resembles and is related to Queen Anne’s Lace but is taller (up to 1.5 meters) and has a yellowish flower crown in contrast to Queen Anne’s Lace, which has a white flower, both of which bloom in July.

The weed resembles and is related to Queen Anne’s Lace but is taller (up to 1.5 meters) and has a yellowish flower crown in contrast to Queen Anne’s Lace, which has a white flower, both of which bloom in July.

A chemical compound that is released from the broken leaves and stems of Wild Parsnip can cause severe burn blisters to the skin when activated by sunlight.

Unlike poison ivy, the reaction caused by contact with wild parsnip sap is not an allergic reaction. Toxin in the sap is absorbed by the skin and then energized by ultraviolet light. The sap is most potent when the plant is in flower. Mild exposure is similar to sunburn. Severe exposure causes skin to blister.

People who come in contact with the toxic sap are prudent to avoid sunlight on the affected area and to wash exposed skin thoroughly with soap and water. Sap that gets into ones eyes is of real concern and should be rinsed immediately, and obviously medical attention should be sought for this and any serious cases.

Poison Parsnip is not generally considered to be as big a problem for pets as usually there is no contact with skin on areas exposed to sun, but caution in coming in contact with the sap that may be transported by a pet is warranted.

The simplest method of control may be to regularly cut the grass, plants and weeds in open areas where it presents before seeding begins in July, or if you wish to leave wild areas uncut, a simple regular inspection and removal by pulling or cutting the tap root (with noted cautions) will control the plant. The plant only propagates via seed.

You can remove them by digging or hand pulling, especially after a good rain or a period of drought. Be sure to wear shoes or boots, long pants, long sleeves, gloves and goggles when you are working near it and dispose of the plants by drying in location (possibly covered) or bagged and dried for a week. Thereafter the plant material should be safe to be treated as garbage (refer to your local authority). Do not compost or burn.

The tall seed plant produces seed in the second year of growth, and with practice one can identify the first year plant for eradication.

As mentioned, the proceeding is a summary of information that is available from a number of different authorities and sources. Please refer to authorized agencies, some of which are referenced below.

Weed Info Canada web site: good info on identification

http://www.weedinfo.ca/en/weed-index/view/id/PAVSA

Leeds-Grenville web site: good info on eradication

http://www.healthunit.org/hazards/dangerousweeds.html

Scott Moffat Councillor City of Ottawa: overall info and disposal procedures

http://www.rideaugoulbourn.ca/wildparsnip/

Zebra Mussels

by Cheryl Savery

In November 2012, Leslie Kirby and Tom Olvet reported seeing what appeared to be a single zebra mussel attached to the thermometer at their dock near Hidden Valley Lane on the South Branch. Kathy Leverette (from Narrows Lane) also reported having seen some zebra mussels attached to the bottom of their boat when they removed it that fall. As far as I am aware, these were the first sightings of adult zebra mussels in Buck Lake. Since then, I have noticed a slow but steady increase in the number of zebra mussels along our waterfront (also on Narrows Lane).

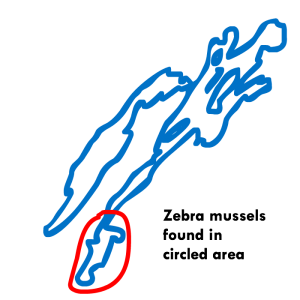

In 2013, I found 3 or 4 mussels. Then in 2014, I found about 40, and alarmingly this past summer I removed several hundred from the water in front of our property. This fall, I decided take out my kayak and survey the shoreline around the south end of the South Branch to see how far the zebra mussels had spread. Based on my observations, it appears that there are now zebra mussels along almost the entire shoreline in the Narrows and south of the Narrows on the South Branch. So far, I saw no instances of large masses of zebra mussels as are often seen in media pictures. Instead they tended to be spread out with approximately 2 to 3 mussels per square foot. I never saw any signs of zebra mussels north of the Narrows. I would be really interested to know in anyone has seen them in any other areas of the lake.

It had been speculated that it was possible that zebra mussels would not be viable in Buck Lake due to the low calcium levels in the water. Water samples collected between 2008 and 2012 indicate that the median calcium concentration in Buck Lake is 22.4 mg/L in the South Branch and 10.5 mg/L in the North Branch. To help me understand what these numbers meant, I searched on the internet and found a paper, “Zebra Mussel’s Calcium Threshold and Implications for its Potential Distribution in North America”. In the paper, they begin by referring to an analysis of over 500 European lakes that reported that zebra mussels were found only in waters with at least 28.3 mg/l of calcium. The paper then hypothesized why we are seeing zebra mussels in North American waters with lower calcium concentrations. The paper summaries a large number of studies on North American lakes and concludes that zebra mussels can survive and reproduce in waters containing less than 25 mg/L calcium, although they may grow and reproduce more slowly. The exact threshold calcium level is not clearly defined and it is likely pH dependent.

It had been speculated that it was possible that zebra mussels would not be viable in Buck Lake due to the low calcium levels in the water. Water samples collected between 2008 and 2012 indicate that the median calcium concentration in Buck Lake is 22.4 mg/L in the South Branch and 10.5 mg/L in the North Branch. To help me understand what these numbers meant, I searched on the internet and found a paper, “Zebra Mussel’s Calcium Threshold and Implications for its Potential Distribution in North America”. In the paper, they begin by referring to an analysis of over 500 European lakes that reported that zebra mussels were found only in waters with at least 28.3 mg/l of calcium. The paper then hypothesized why we are seeing zebra mussels in North American waters with lower calcium concentrations. The paper summaries a large number of studies on North American lakes and concludes that zebra mussels can survive and reproduce in waters containing less than 25 mg/L calcium, although they may grow and reproduce more slowly. The exact threshold calcium level is not clearly defined and it is likely pH dependent.

It remains to be seen how big a problem the zebra mussels will become in the next few years. Will they become an incredible nuisance attaching to all boats and docks and rocks throughout the entire lake, or will they continue to survive in lower numbers only?