Early History of Buck Lake

It is generally agreed that First Nations peoples began to occupy southern Ontario, including the area north of Kingston, after the retreat of the last Ice Age (11,000 BCE). Unfortunately, according to Ron Vastokas, the very earliest inhabitants of Frontenac County left few remains.[1] We know that the first inhabitants came from the Great Plains (the area between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains in the United States) and it is thought that the large game animals that colonized the area around the Great Lakes attracted them. Around 9,000 years ago, the local climate began to warm, bringing more species of plants and animals – and the human population increased. A population that was predominantly reliant on hunting now began to trap, fish and gather seeds, berries and tubers. The period from seven thousand years ago until three thousand years ago is known as the Archaic Period when two cultures existed in Ontario – the Laurentian culture of southern Ontario and the Shield culture, coinciding with the geography of the Shield.

By the late Archaic Period, “we find evidence of increased population growth, noticeable adaptations to regional resources, widespread trade, and the appearance of several technological innovations – namely the making of clay pots.”[1] The Woodland period of prehistory begins around three thousand years ago. At this time, the Shield cultures were still very much dependent on hunting and fishing, but in the Laurentian cultures we see a “greater variety and richness in material goods and ceremonial life.”[1] Another important arrival made its way from the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys in this period – the growing of maize (corn). By about a thousand years ago, the “hunting and gathering communities of southern Ontario were settling down into villages and were beginning to raise corn, beans, squash and tobacco.”[1] These communities evolved into the Iroquoian tribes that we read about, as described by the French explorers and missionaries. First contact between the First Nations of the area and Europeans commenced with the explorations of Samuel Champlain in 1615 and the settlement established by Count Frontenac at Cataraqui (Kingston) in 1673. Control shifted to the British with the arrival of the Loyalists in 1783 who acquired the lands behind Kingston from the Ojibwa Mississauga “as far as a man could travail (sic) in a day,” by the Crawford Purchase of 1783. These lands were the traditional hunting grounds of the former occupants, the Haudenosaunee (Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy) and the Anishinaabe (Ojibway, Mississauga and Algonquin) peoples who occupied the region at the time of the arrival of the British.

With the establishment of the province of Upper Canada in 1791, the survey of lands commenced and, as early as 1792, Alex Aitken was instructed to survey lands to the rear of Pittsburgh, Loyalist Township. He abandoned his task because “I would be putting Government to a useless expense to Survey lands that will never be settled.”[2] Samuel Wilmot took over from Aitken and he too declared that the land “cannot be settle (sic), being either rocks or swamps.”[3] In 1821 Samuel Benson was charged with surveying Bedford

Township and three years into the project he gave up, explaining that the “land is so bad that there can never be settlement affected (sic) on it.”[3] All of these initial surveyors expressed serious doubts about the quality of the land for agriculture and settlement because they were encountering the Frontenac Axis of the Canadian Shield that extended from the north, through Kingston’s hinterland and extended across the St. Lawrence to the Adirondacks. The lands surrounding Buck Lake were considered unsuited for pioneer settlement, best developed as timberlands, and long remained a pristine wilderness until their beauty attracted new attention.

Field notes from the original surveyors indicate that people were living in the area at the turn of the 19th century, but it is likely they were squatting on land that was not owned by them. As Fuchs and Barber note, “driven by reasons of their own – desire, poverty, sheer lack of alternatives, curiosity, single-mindedness, antisocial tendencies, wanderlust, ambition – they had followed a mere shadow of a trail”[3] into the wilderness. Rankin’s 1832 field notes confirm that settlers must have frequented the area before then because he makes reference to the names Buck, Bear and Draper Lakes. It is unclear who named the lakes originally or precisely when people started to settle the area. Although the area was still very remote, we do know that Chaffey’s Mill was already established on the Massassauga Creek in 1826 and Benjamin Tett was operating a mill, a store and a distillery at Bedford Mills as early as 1829, according to his own personal notes.

It wasn’t until the passing of the Baldwin Act (formally known as the Municipal Corporations Act) in 1849 that official communities were formed. For the Buck Lake area, the most important byproduct of the Baldwin Act was that road construction began in earnest. In the early 1850s the Kingston hinterland was virtually without road transport. Thanks to the efforts of Sir John A. Macdonald and John Counter, the Mayor of Kingston at the time, a company was established in 1850 to build a legitimate road to Perth, Ontario. Progress was slow, but it was reported in the British Whig that in 1855 James Campbell had sold some 30 lots on the new Perth Road in what would become New Inverary[3] (Inverary today). Inverary was as far as the stagecoach travelled at the time, so people had to either drive by horse or walk from Inverary to Kingston. The Perth Road was winterized in 1856 and it is clear that the road improvement was the catalyst in opening up the backcountry. Perth Road Village was first settled in the mid-1800s but grew substantially in 1870 when Christopher Roushorn discovered lead in the area. At the time, the village was known as Stoness Corners, after founders James and Jabez Stoness. The second major factor in the settling of the backcountry was the Great Famine in Ireland. Between 1845 and 1852, a million people emigrated from Ireland, some of whom arrived in Kingston and sought cheap property in the hinterland.

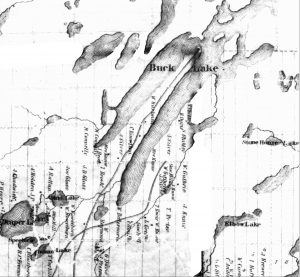

In 1860, H.F. Walling produced the first map that depicted the area well. On this map we can see 10 lots that have been patented to various individuals or families, roughly as far north as where Norman Lane is today. The following names were included on the 1860 map: P. Woodcock, S. Shibley, E. Davis, J. Silver, Mrs. Ennis, C. Smith, W. Batermore, I. Brook, M. Connolly, C. Knowlton. The map also shows us that some of these landowners had already constructed buildings at the time of the mapping.

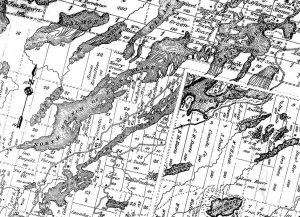

Curiously, by the time of the next mapping in 1878 by the Meachem Map Company (note the very distorted sizes of the North and South Branches on both the 1860 and 1878 maps), very few of the names from 1860 were still evident in the area. The 1878 map shows people living all around both the North and South Branches of Buck Lake, including a concentration of residents along Perth Road from Buck Lake past Devil Lake. The names on this map include: David Sears, H. Sears, William Sears, Henry Green, William Green, Jabez Stoness, N. McCallum, William See, Benjamin Aykroyd, I. Cobett, James C. Darling, Joseph Darling, C.W. Darling, Joseph Harris, George McFarlane, George Teepell, Thomas Votrey, Thomas Galliger, George Ennis, John Ennis, James Hamilton, John Richardson, John Buck, S. Hartman, H. Scott, S.W. Davis, W.E.M. Davis, S. Ennis and James Rutledge. There is one particularly dark story from these early settlers. Elijah Vankoughnet murdered John Richardson in 1881 at his home on Buck Lake. For the murder, Vankoughnet entered the history books as the last man hanged in Frontenac County. At this point a small amount of land was still controlled by the Canada Company, a large private British company established in 1825 to aid in the colonization of Canada. The Green Family was among the first settlers of the area, having arrived from either Ireland or Chicago. The Green Family was made up of hunters, trappers, fishermen and guides. An old Green family cemetery still sits on Roushorn Road and direct descendants of the original settlers still live on the lake.

[1] Ron Vastokas, “Before Written History,” in County of a Thousand Lakes, ed. Bryan Rollason (Kingston: Frontenac County Council, 1982), 10.

[2] Brian S. Osborne and Donald Swainson, Kingston: Building on the Past for the Future, Kingston: Quarry Press, 2011, 167.

[3] Barber and Fuchs, Their Enduring Spirit, 25.